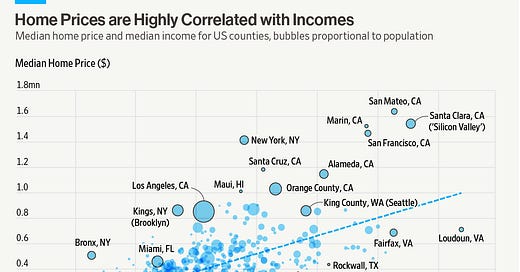

Welcome back to Home Economics, a data-driven newsletter about the American housing market. Today’s article is about the relationship between household incomes and home prices. Subscribe/upgrade here:

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Home Economics to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.