Welcome back to Home Economics, a data-driven newsletter about the housing market.

2023 was a big year for us. We rebranded, grew our subscriber base by 500%, and published dozens of articles about everything from seasonal patterns in home sales to the demographics driving housing demand.

As the year winds down, we're taking a look back at five analyses we published that helped differentiate us from the consensus. We stand by them all heading into 2024.

We’re looking forward to bringing you more useful insights, beautiful visualizations, and smart tools in the months ahead.

Until then, wishing you a healthy, peaceful, and happy New Year.

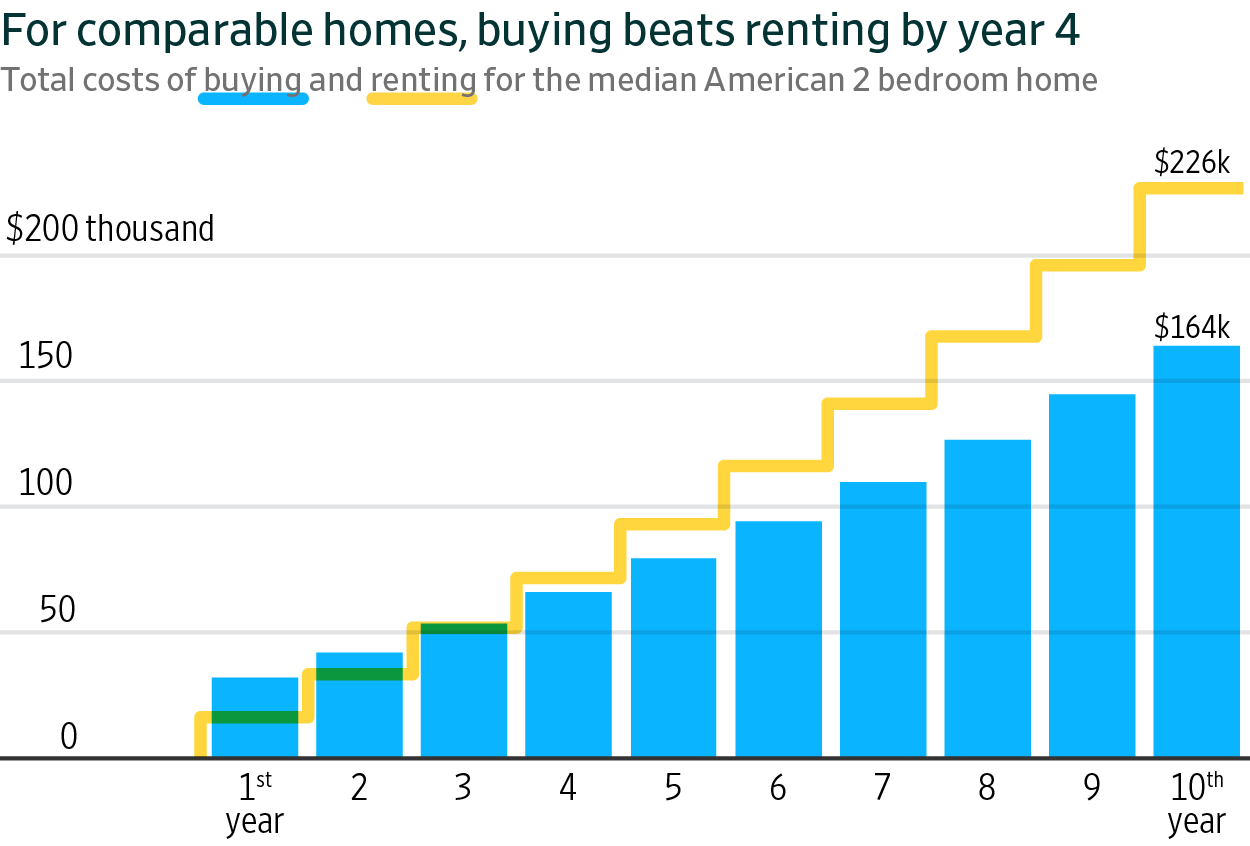

As interest rates rose throughout the year, we were inundated with stories touting the attractiveness of renting over buying. We took issue with the cursory analyses, and developed our own Buy versus Rent calculator that showed that, for reasonable horizons and under most conditions, buyers will still end up better off than renters.

Buy or Rent | A Renter’s Paradise—but for How Long? | Growing Pains for Home Prices | The Home Economics Buy or Rent Model

We argued in The Financial Times that, even if prices stabilize and interest rates decline, Millennials will still find it harder to continue to make inroads into homeownership. The reason: a major demographic shift underlying the tight housing market won’t recede for years.

Millennials and Boomers are Competing for Homes. Guess Who’s Winning | Article in The Financial Times

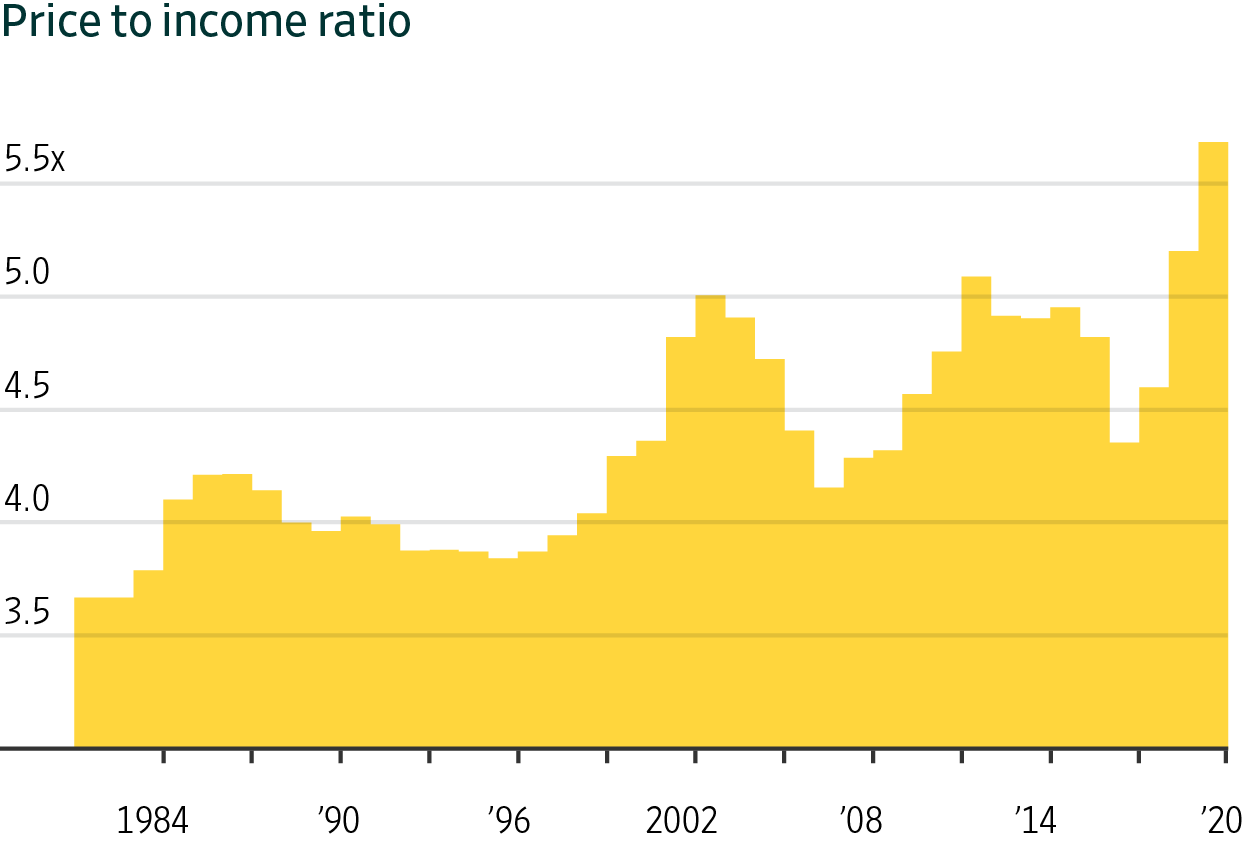

We showed how home prices are now historically stretched compared to rents and incomes, and argued that a period of consolidation lies ahead: home prices will likely grow more slowly than rents and the wider economy. But even if we get a softening in prices for home owners, finding affordable housing will still remain a significant challenge for many Americans. As we approach the presidential election at the end of next year, we expect the housing crisis to feature heavily in the conversation.

Growing Pains for Home Prices | Expensive Housing is a Secular Trend, not a Cyclical One

Mortgage lock-in prevents home prices from adjusting to the shock of higher financing costs, and exacerbates already-low geographic mobility. But this needn’t be an intractable problem. We wrote about how the only other country in the world that finances mortgages with bonds—Denmark—is a model for how policy changes could alleviate mortgage lock-in and other problems with the American housing market.

Why Denmark's Housing Market Works Better than Ours | Everywhere you go, always take your mortgage with you

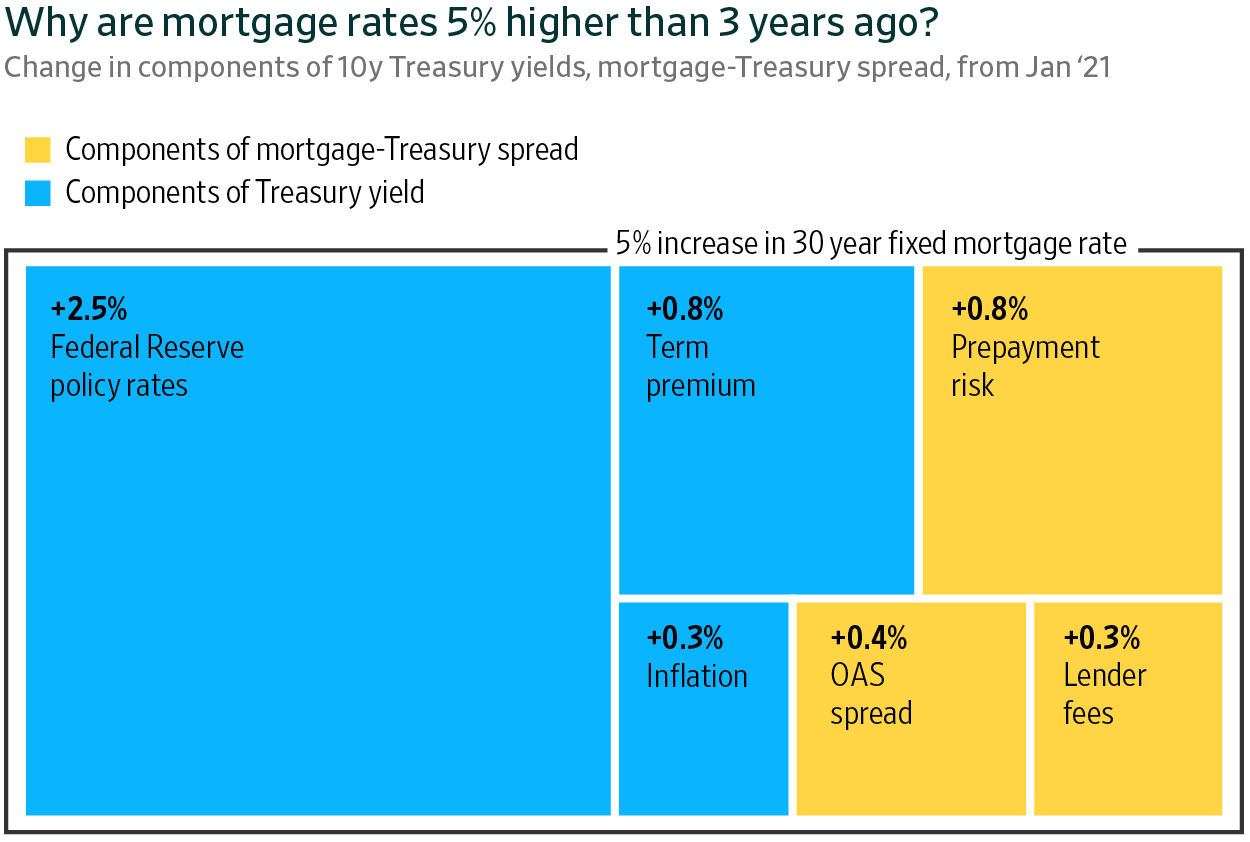

On October 25th—the day mortgage rates peaked at just under 8%, and a full week before influential hedge fund managers like “the bond king” Bill Gross declared interest rates too high—Home Economics published the first of a three-part series arguing mortgage rates would soon fall. We showed how the end of Fed hiking and declining inflation, uncertainty, and prepayment risk would all combine to lead rates substantially lower. With mortgage rates now close to 6.5%, there is still room for further compression.

Mortgage rates are set to fall | A Smaller “Term Premium” means Lower Mortgage Rates | Another Reason Mortgage Rates will Fall